No Bad Memories

Studio → Blog

The internet is (not) forever

Posted Tuesday, September 30, 2025

Last week's notes on the SIGGRAPH '79 Film and Videotape Retrospective were part of an experiment in moving my blog toward something I've long intended for it to be: a studio log where I can take notes on and organize reference material related to my practice.

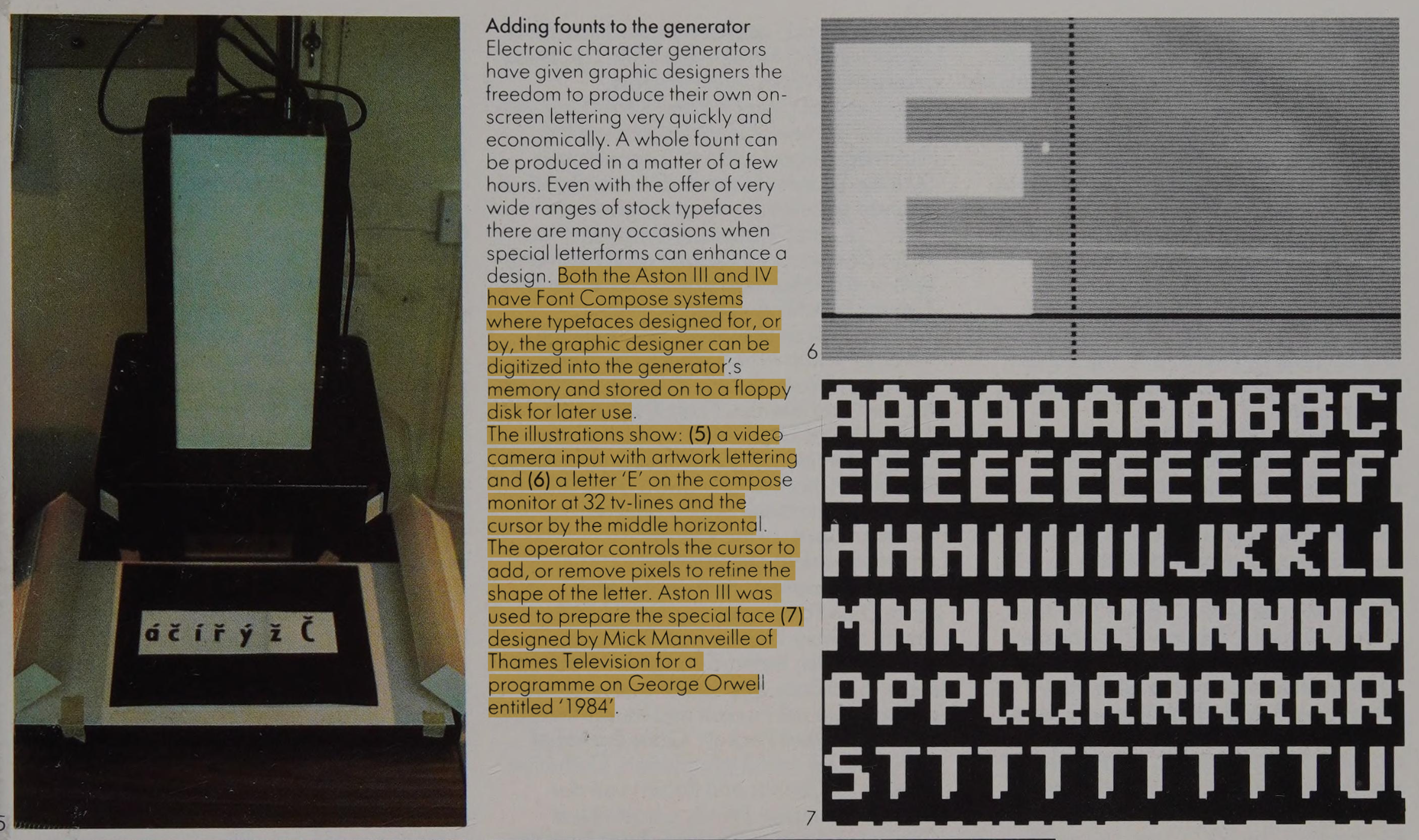

I've been doing a lot of PDF and website downloading lately, fueled by an uneasy feeling that the knowledge avalanche all around us is burying decades and centuries of texts with heaps of incoherent, profit-driven AI slop. So I read through old scanned magazines, catalogs, out-of-print books, and save or highlight little snippets that interest me.

I appreciate how much of this is available through archive.org, though I've been saving offline copies, too, in the event that the unthinkable happens and all their content is zapped out of existence. (I suppose it will happen at some point, but hopefully not in my lifetime.)

MyLifeBits

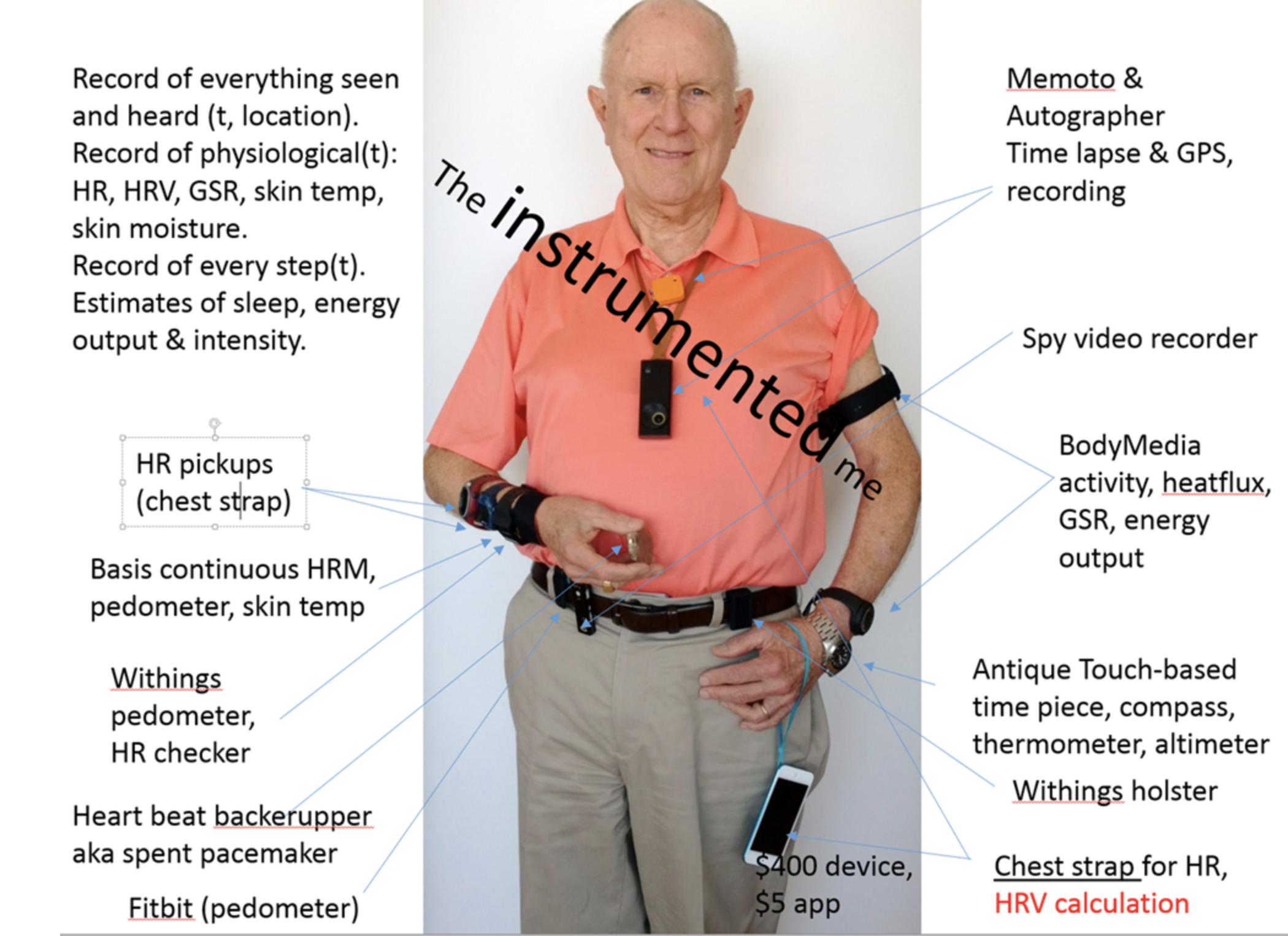

I don't know if you call this archivist's instinct, paranoia, practical preparedness, or what. But I do remember being quite struck last year reading about Chester Gordon Bell, a computer engineer who designed several of the PDP minicomputers. In the 1990s, he helped found Microsoft Research, where he explored the fields of telepresence and quantified self/lifelogging. His research project was called MyLifeBits, which was an effort to develop a software platform to store all manner of personal telemetry, media, etc. as a digital backup for one's life. Bell wrote several books and gave a whirlwind of talks about this work. In 2002, the BBC said this of the project in an article titled "Microsoft plans online life archive":

Microsoft researchers are working on ways to create a "back-up brain" that will do a much better job of containing and cataloguing every picture you take, document you write or conversation you record. The scientists collaborating on the project believe that the database of your life could hold a vast array of items that are automatically catalogued and as easy to search as Google. If it proves successful, the project could realise the dreams of hypertext visionary Vannevar Bush, who first floated the idea of a lifestore more than 50 years ago. The MyLifeBits research group is based at Microsoft's research lab in San Francisco.

New Scientist magazine reveals that Gordon Bell, one of the scientists driving the MyLifeBits project, is already putting as much material as he can in a directory of his life. It reports that every e-mail message Mr Bell sends and receives is already being stored along with everything he reads or buys online. Mr Bell has also started recording all phone conversations and any meetings he attends.

MyLifeBits was never finished. In later years, Bell conceded that the smartphone would come to fulfill the role imagined for MyLifeBits, and presumably his goals for the work shifted or shrank.

Bell died in 2024. His website is still online, though links are slowly beginning to break. And while Bell's website provides a nice catalog of his publications and talks, it's unclear what happened to the decades of telemetry and memories he collected on his own life.

To test the application, Bell is downloading his own life onto a hard drive at the [Microsoft] media lab. His database spans more than a century of data: the first entry consists of photographs of his parents taken as children in 1900 and the last entry (as of Thursday morning) was a website he browsed before he was interviewed for this article. —"Saving Your Bits for Posterity," Wired, Dec. 6, 2002

The siren song of cataloging

There's an obvious cautionary tale here: Don't build your legacy (or catalog, if you prefer) at the expense of building your life. It's especially relevant to those among us who experience near-obsession with modularity, information structure, and preservation, cheered on by the possibilities of self-made software. Perhaps we love the history of hypertext, we write our own programming languages, we prefer Markdown or plain text over proprietary file formats. We invoke Vannevar Bush and Ted Nelson, nevermind the irony of the Xanadu Project's fate as a perpetual demo. We may even try, at some point, to develop some overarching "everything machine."

"What have you been up to lately?"

"I'm writing this... software."

"Oh, cool. What's it do?"

(Eyes widen) "Everything."

"What do you mean everything?"

(Eyes close) "It does everything. It's, like, a self-compiling system for making open-ended systems. OK, OK, imagine that—" (sips coffee) "You know the hypertext paradigm? Never happened. The web browser, the iPhone, man, NONE of that shit ever happened. THAT'S what I'm building. It's not software, really. It's more like an operating system built on a conceptual framework. So it can be anything, everything, simultaneously. And it's really simple to use. Well, it will be when I finish it." —my recent post on merveilles.town

I tumbled down these paths recently. They're fun, but they're not fruitful, for better or worse. I'm now realizing that I can collect and preserve things without the full gravity of building "C:\Dropbox\My Lasting Legacy.zip." Hence: studio log. Excerpt what's relevant, save it offline, maybe mirror it online, and then actually use it for something. Find a cool animation technique from the 70s that was made obsolete by computers? Document it, write about it, then try it. That's the plan, anyway.

The internet is (not) forever

The other cautionary tale: what's online isn't online forever, even when you've dedicated decades to explicitly working toward digital preservation as Bell did.

One side of that coin is "aaaah, quick, print out all the websites and put them in 3-ring binders!" (Y'all have 3-ring binders, still, right?) But the other side is, "ehhh, this'll be offline soon enough." And that's the freeing side that reminds me that my logs don't need polish or editorial consistency. They can just be however they are, warts and typos and all.